Cache

Summary of the Story

By Jon Erlandson, Archaeologist, Professor of Anthropology, and Executive Director

Museum of Natural & Cultural History, University of Oregon

From the Island of the Blue Dolphins: An Extraordinary Archaeological Discovery on San Nicolas Island

As an archaeologist I’ve spent nearly 40 years studying the deep history of coastal areas around the world, from California and Alaska, to Oregon, and Iceland. I’ve been fortunate to make some amazing discoveries over the years: 12,000 year old Paleocoastal artifacts left by some of the First Americans following a “kelp highway” from northeast Asia to the Americas; a Viking church and longhouse dated to AD 1000; and excavations at Alta California’s missions and presidios. Having read Island of the Blue Dolphins as a child, the unexpected discovery of two redwood boxes on San Nicolas Island may be the most extraordinary of my career.

On a sunny fall afternoon in 2009, I was walking the actively eroding sea cliffs of San Nicolas looking for camp sites dating between 8,000 and 12,000 years old. So far, no island archaeological sites have been dated to more than about 6,000 years ago, but a few isolated artifacts known to be much older are stored in poorly-documented museum collections. As I meandered along the sea cliff, examining ancient soils buried below younger sand dunes, I looked down and saw a large bone sticking out of the cliff face. Thinking it was a Pleistocene whale fossil eroding from a raised beach, I climbed down the steep cliff for a closer look. Under what turned out to be a much younger whale rib, I was surprised to find an old and heavily weathered wood box. The bottom of an old Nicoleño-style water bottle made of woven basketry coated with tar rested on the cliff face nearby.

The exposed end of the small box had fallen off and looking inside I saw something shiny and picked out a piece of old green bottle glass. Next I picked out a bead made from soapstone, a brass button, and a carved soapstone effigy. Then I thought “You idiot, stop pulling things out of the box!” I knew the box was special, but I had no way of knowing at that moment just how spectacular a discovery it was. I found my colleagues, and together we examined the box, the cliff face, and its larger setting. Federal and state laws protect such discoveries and it was clear that with the next big storm the sea would destroy it.

We quickly changed plans for the day of our trip. Early the next morning, perched on a narrow ledge above a steep sea cliff and rocky beach, we carefully uncovered two small boxes made from split redwood planks. Redwood logs from northern California, carried south by coastal currents, washed up on island beaches, where for millennia, the Nicoleño and their island neighbors used wood split from such drift logs to make sophisticated boats, containers, handles for tools, and other objects. Just outside the boxes, we found two whole woven basketry bottles waterproofed with tar, very similar to one Juana Maria had with her when “rescued” by George Nidever and his group of sea otter hunters in AD 1853. Once they were partially exposed, we found that both boxes were rectangular, with a bottom and four walls made of thin redwood planks glued together with natural beach tar. Wood planks were laid on top of each box but not glued shut, suggesting that they were not ritual offerings, but used by someone who returned periodically to add to or take things from the boxes. The whale rib, several feet long, was probably a marker and may also have kept the box lids from being blown away by strong winds that often buffet the island. After they were fully exposed, we pushed flat sheets of aluminum under each box, carefully lifting one then the other and placing them in cardboard bankers boxes for transport, with contents intact, to a U.S. Navy archaeology lab on the island. As we moved one of the redwood boxes with its lid removed, the soil inside shifted and several artifacts could be seen. Among them, I focused on a large leaf-shaped blade ground from a piece of slate, along with a bone harpoon tip, barbed on one side, with a line hole drilled near its base.

Having worked in Alaska for many years, I instantly recognized these as artifacts made not by the Nicoleño, but by native peoples of the Pacific Northwest. Later four barbed bone toggling harpoon heads were found in the boxes—three with corroded metal blades still intact in their slotted tips—made in a style unique to Koniag and Aleut (Alaska Native) hunters of early historic times. The harpoons are smaller than Alaska Natives used for hunting seals, which led me to believe they were used for hunting sea otters. Similar Native Alaskan artifacts were found on San Nicolas and other California Channel Islands more than a century ago by some of the first scientists and surveyors to visit the islands. Left behind during the historic fur trade era, when Alaska Natives were brought to California by Russian and other European or American entrepreneurs to hunt sea otters whose fur pelts were extremely valuable in China, these rare artifacts were stored in museums and could not be linked to specific sites on the islands. With my experience in Alaska and knowing the history of the fur trade era and the clash of cultures it created, I had always dreamed of finding a Native Alaskan harpoon on the Channel Islands. Since no modern archaeologist had ever found one, I never thought this dream would come true. It was a landmark day on San Nicolas Island, but what came later was even more exciting.

Later, in the Navy lab on San Nicolas, the contents of the two redwood boxes were meticulously excavated by my colleagues, the entire process filmed and carefully documented. What came out of the boxes was an extraordinary set of roughly 200 objects, including a mix of artifacts of Nicoleño, Native Alaskan, and Euro-American origin. These included many finished tools and ornaments, some of them rarely preserved or seen by archaeologists: Alaskan and Nicoleño-style bone harpoon heads, several stone knives set in redwood handles, ornaments made from shell, bone, and soapstone, a carved stone pipe with a wad of tobacco in the bowl, two spectacularly barbed abalone shell fishhooks, containers made from whole abalone shells, bird bone flutes, arrowheads made from both stone and historic bottle glass, and much more. Also included was a diverse array of unfinished or more utilitarian artifacts, as well as raw materials of stone, bone, shell, glass, and metal. Most of artifacts from in and around the boxes—as well as the boxes themselves—seem to have been made by Nicoleño people, some of them using materials like bottle glass that only became available in historic times. The mix of finished tools, unfinished artifacts, and raw materials suggests that the boxes are part of what some archaeologists call a “utilitarian cache,” a group of objects stored or hidden in a strategic place, intended for use in the future.

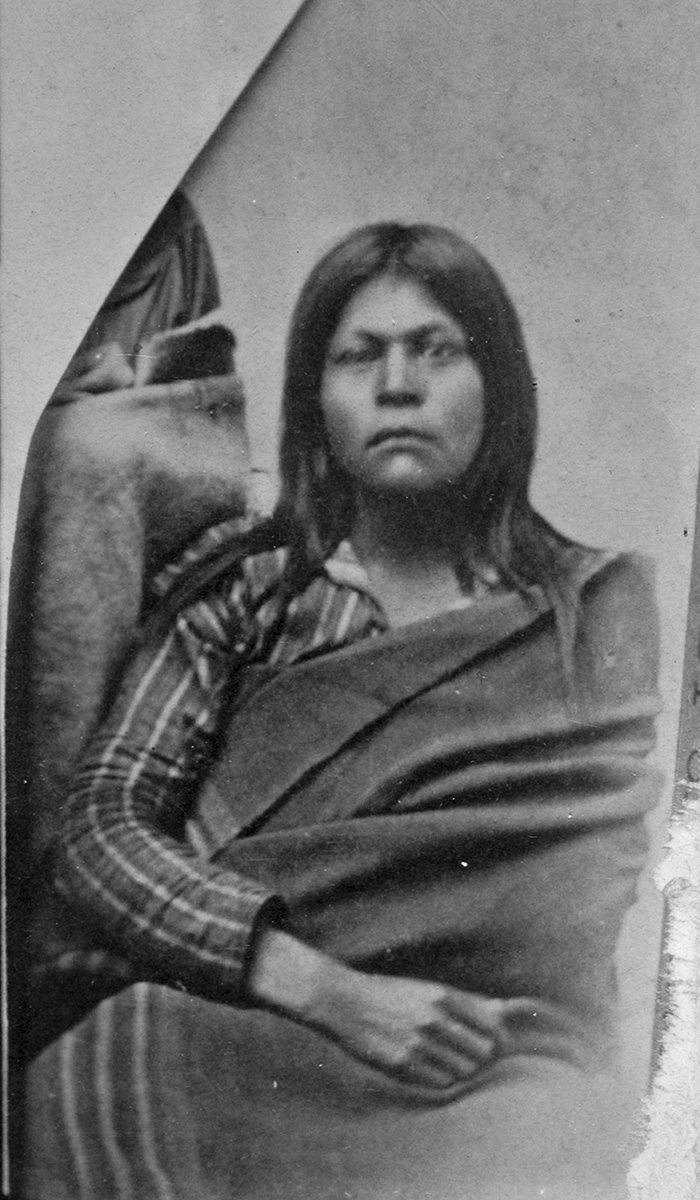

Who left the boxes and their contents behind? We may never be able to answer that question with certainty, but we know from historic documents that Russian fur traders brought Koniag hunters to San Nicolas Island around AD 1814, where they clashed with the Nicoleño (Island Tongva) people, leading the Spanish Mission fathers to evacuate the few surviving Nicoleño people to the mainland in AD 1835, except for the Lone Woman herself. Were the boxes and their contents used by the woman later christened as “Juana Maria”? Again we may never know for sure, but analysis of the artifacts suggests that they were stashed after the Koniag left in AD 1815 and before the Lone Woman was taken from the island in AD 1853. If the boxes and their contents were not hidden and used by Juana Maria—as I suspect they were—they must have been used by one of the few Nicoleño remaining on the island during the twenty years after the Russians and Koniag left and everyone but Juana Maria was evacuated from the island. Intriguingly, we know from Nidever’s description of finding the Lone Woman that she had materials stashed in a variety of places on the island.

Imagine living completely alone on a remote island for eighteen years—even the fictional Robinson Crusoe had his friend Friday! What would you need to survive and how would you get it? The contents of the redwood boxes and the water bottles hidden in a recessed nook in the sea cliff seem to have been scavenged from across the island, some of them from abandoned villages of the Nicoleño or Koniag, others as flotsam from local beaches. They may have served as insurance for Juana Maria, storage boxes filled with a wide variety of tools, other artifacts, and raw materials she knew would be invaluable for a woman living alone on a small and remote island located far off the California Coast. Whether the boxes were used by Juana Maria or her Nicoleño tribal family, their amazing contents provide a rare opportunity to explore the connections between archaeology, history, and the lives of real people caught up in the tumult of California’s early historic period, as colonialism and globalization changed their world forever.

Video Segment : Cache

Image Gallery

Teacher-Created Lessons and Resources

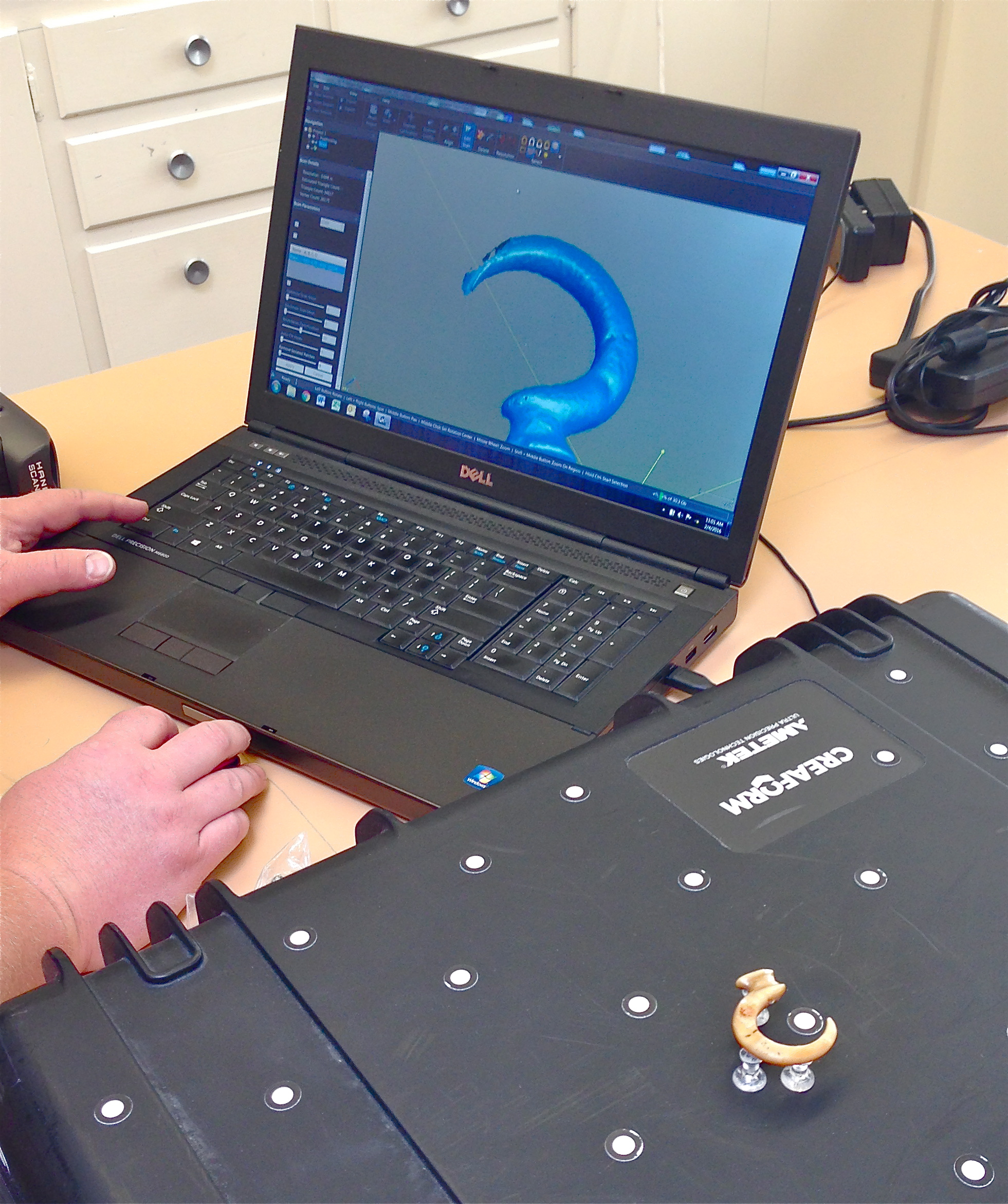

3D Scan of Artifacts

3D Scans of artifacts brought by the Lone Woman back to the mainland were made possible through the generous support of:

The Nidever Family Collection (Donut Stone)

Marla Daily - Santa Cruz Island Foundation

The Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

(Arrow Head and Abalone Fish Hook)

Jan Timbrook

American Museum of Natural History (Whale Baleen Hairpin)

Dr. David Hurst Thomas, Ph.D, D.Sci, RPA

GoEngineering.com

** 3D object print files available for download below. Please fill out the form to access the files.

Additional Resources

from Jon Erlandson, Archaeologist, Professor of Anthropology, and Executive Director

A website about all things Channel Islands

Island of the Blue Dolphins Wikipedia

San Nicolas Island Archaeology, California Islands Symposium 2012.

Morgan, Ron. 1979. An Account of the Discovery of a Whale-Bone House on San Nicolas Island. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 1(1):171-177.

Erlandson, Jon M., Lisa Thomas-Barnett, Rene L. Vellanoweth, Steven j. Schwartz, and Daniel R. Muhs. 2008. From the Island of the Blue Dolphins: A Unique Nineteenth-Century Cache Feature From San Nicolas Island, California. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 8:66-78.

Tongva: People of the Earth. Haramokngna American Indian Cultural Center.

West of the West: Tales from California’s Channel Islands

Erlandson, Jon M. 2008. Racing a Rising Tide: Global Warming, Rising Seas, and the Erosion of Human History. Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 3:167-169.

University of California Press - Island of the Blue Dolphins - Complete Readers’ Edition

Lone Woman and Last Indians Digital Archives

Download Teaching Materials

All of the teaching materials are free to use for educational purposes. All we ask for is to fill out the form below with some of your information. The download links will appear after you successfully submit your information. Thank you.